The Viennese start-up Vienna Textile Lab uses microorganisms to dye textiles in a sustainable way. This is even relevant for outer space.

Cotton fields soaked in pesticides, factories in low-cost countries with low environmental and social standards, emission-intensive manufacturing processes that use a lot of water, fossil raw materials and persistent chemicals: the textile industry has a lot of work to do if it wants to take its ecologization seriously. Circular economy, green chemistry and bringing production back to Europe, where it is to become more environmentally friendly through the use of high-tech, are still in their infancy.

Blue jeans mostly synthetically dyed

Dying the textile fibers is one element on the path to T-shirts, dresses and jackets, which is characterized by many process steps. Conventional manufacturing techniques are largely based on fossil, but also partly on vegetable raw materials. For example, the indigo pigments that traditionally dye jeans blue come from the plant of the same name, but are now mostly synthetically produced.

In addition, however, a third line is currently being established, which is based on the use of microorganisms. Certain metabolites of microorganisms are at the same time pigments, in some cases even identical to those obtained from plants. The Viennese start-up Vienna Textile Lab (VTL), founded in 2016, is one of the companies developing a technology platform for dyes made from microorganisms. The first products should be on the market in 2025.

“We can see that the textile industry has a strong interest in the new dyes. In the EU, approaches are being sought that will make the economy less dependent on global supply chains – the corona crisis and the war in Ukraine have also contributed to this,” explains the company founder Karen Fleck. “The microbial approach offers the opportunity to make the dyeing process much more resource-saving and environmentally friendly. The required bioreactor can be located anywhere without significantly changing the production costs – even in an EU country.”

From TU Vienna to your own start-up

Fleck himself studied technical chemistry at the TU Vienna, followed by a doctorate at the RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. Her first career took her into the energy industry, and she actually wanted to start her own company in this area. But things turned out differently: Fleck got to know the microbial dyes in the Textile Lab Amsterdam, a kind of open laboratory that makes a wide range of textile technologies accessible in workshops.

The interest in the ecological production process gave rise to a business idea: “The VTL is now one of the first wave of start-ups dedicated to the bacterial dyeing of textiles,” says Fleck. The microorganisms used in the start-up come from the soil, the sea or other aquatic environments.

“Bacteriograph” delivers

However, Fleck and her team do not have to search for them themselves. The main supplier for the paint producers is Erich Schopf. As a “bacteriographer”, the Viennese has been collecting microorganisms for decades. They are used, for example, for artistic purposes – for painting pictures. “For us, the bacteriograph collection, which is probably unique in the world, is an absolute stroke of luck,” emphasizes Fleck.

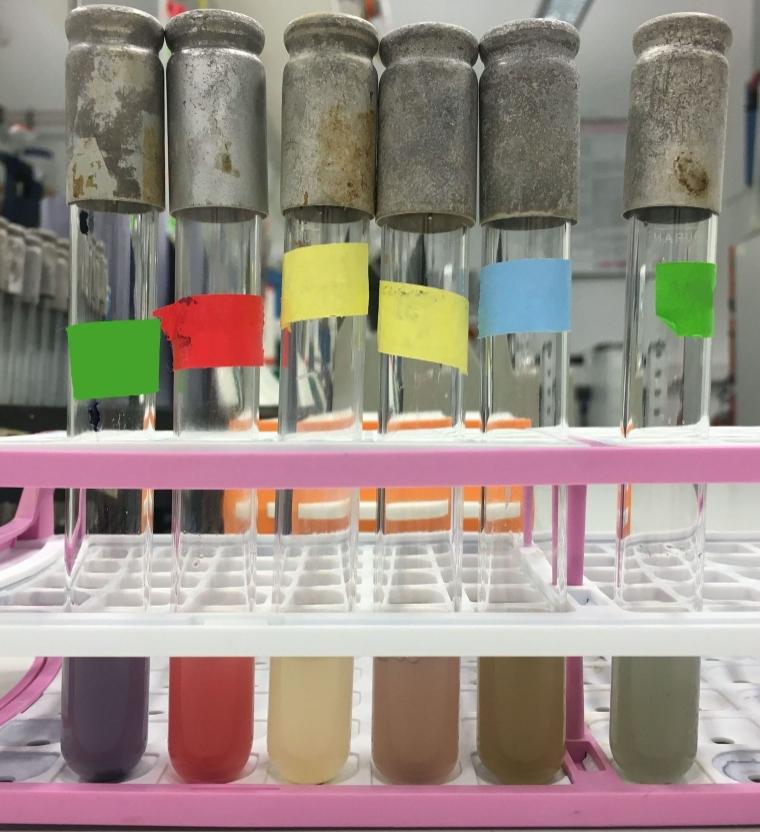

The start-up immediately unleashes the bacterial strains on various textile fibers in order to test the dyeing effect and to be able to identify affinities for certain fibers. Promising candidates are genetically identified. The requirements are high: “Today, colors are perfectly matched to the fibers. In addition, they must work together with a large number of improvers and additives that provide crease protection or greater durability, for example,” says Fleck.

Microorganisms with high potential are being researched in detail. How can the trunk be optimally cultivated? How to maximize color production? And how should the final product be chemically formulated? Many questions of this kind need to be answered. Even if genetically modified microbes deliver a maximized color output in the future, Fleck assures that there will always be an offer for customers who want to do without this form of genetic engineering. The research of the start-up is supported by the Austria Wirtschaftsservice (AWS) and the FFG funding agency, among others.

Great demand from the textile industry

“In the end, there should be products that can be used in many different areas of future textile production,” Fleck sums up. With an emphasis on “future”: “The technologies used are currently undergoing major changes. For example, new, particularly water-saving processes are being developed for a more efficient dyeing process,” explains the founder. It is important to be prepared for this future.

Fleck cannot complain about a lack of interest in the textile industry. “Although we don’t have a certified product yet, the industry is already giving us a lot of support. There are more projects than we can handle,” explains the founder. “It’s an exciting exchange that – also compared to my previous job in the energy industry – is very feminine. Sometimes ten female technicians sit at the conference table.”

Clothing for space

The use of microorganisms as a production system in the VTL is not limited to textile dyes. Projects that the start-up has implemented with the space agency ESA, to which Austria’s Ministry of Climate Protection also makes annual financial contributions, and the Austrian Space Forum (ÖWF) give a foretaste. The focus was on functional substances that have an antiviral or antimicrobial effect – after all, there is no washing machine for astronaut clothing. Laundry is worn for a long time and then thrown away.

“It was about the innermost layer of space suits. The textiles should have an antimicrobial function so that they don’t get dirty as quickly,” says Fleck. Biotechnological research aims to master the challenges of advanced space travel. “It’s about how materials can be produced in space or on other celestial bodies that are produced on Earth using petrochemistry. Because there is no crude oil on Mars.”